However, the most pressing questions that need to be addressed today relate to AI art, because it is already being used by publishers, including Tartarus Press. Some AI art can be incredibly good, although it is not always recognised that some experience of writing the correct prompts is needed, and that digital re-touching is almost always required (the analogy is with editors who work on AI text). Is AI art likely to damage the livelihoods of artists? Almost certainly, especially commercial artists. For publishers, it is another alternative to conventional, hand-produced art in exactly the same way that photography became an alternative at the end of the nineteenth century, through to digital art in the early twenty-first century.

AI art is a powerful and beguiling tool, but those using AI are not artists. Rather, they are akin to old-fashioned art directors who would previously have had discussions with a human artist as to what kind of image was required and achievable for a specific brief, asking for alternative options to consider, and fine-tuning the result. It is possible to generate good quality AI images in a fraction of the time and cost of working with a real artist, but AI art generated with simple prompts is easily recognisable as such by anyone who has used it for a short time. The creator of AI art has to be aware of such failings as its inability to generate hands with the expected numbers of fingers and thumbs. (In our field of weird and strange fiction, the errors in AI art generation, may, though, produce unintended and atmospheric results!)

Before we go any further, there is a major ethical discussion to be had about copyright. Artificial Intelligence programmes ‘learn’ by feeding indiscriminately and voraciously on information supplied to them. It is possible to simply ask for a picture to be created in the style of an established artist, and this not only feels wrong, but any attempt to pass the work off as being by that artist is obviously illegal. This, though, is not a modern dilemma—the art world has had to grapple with similar problems down the centuries. There have always been ‘schools’ inspired by successful artists, outright imitators, and those who study the work of predecessors which they then attempt to improve. One major problem is that AI in its text and art forms is unable to ‘show its workings’ (as maths teachers still require).

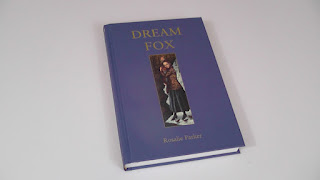

There will always be a demand for artists using traditional materials and media, and many artists feel compelled to draw and paint whether or not they receive employment or recognition. Times will be getting much more difficult for them, but that has been the case not just since the invention of lithographic reproduction and photography, and most recently since digital artists appeared on the scene. Artists have always found that they need to adapt—very few work in a way that could be considered ‘pure’, standing at an easel with their subject in front of them. At Tartarus Press we have very recently been working with an artist who paints subjects in oil inspired by their own imagination, another who uses oils and works from photographs, another who draws in pen and ink based on all manner of existing images, and another whose work is entirely digital, but who does not use AI. Few artists are ‘pure’ in their art—they are on a spectrum, not only for how they conceive imagery, but how it is created and manipulated . . . and the furthest boundary of that spectrum has just been moved further away again in a manner we could not have conceived of only a few years ago. I am aware of artists who now use AI to inspire conventional artwork that is rendered by hand on paper.

To sum up, AI is here, and it isn’t going away. We believe that it should be possible to work with it ethically and harness its many possibilities. And we will also continue to work with real, living artists!

* This is not the place to discuss the concerns that AI might be used to manipulate our thoughts and even control our lives. There have always been information and news providers with biases and agendas, and just because their dubious content can now be generated by computers rather than people doesn’t alter our need to be vigilant. At all times, even before the advent of the internet and digital fakery, we have had to be wary of who is trying to exert influence by offering partial information or downright lying. To really understand the dangers of the mass media, we have to go back to Caxton and the first printing press.