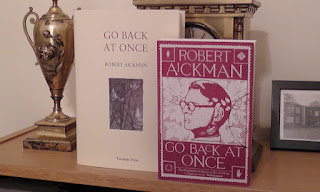

Go Back at Once, published by Tartarus Press (2020) and And Other Stories (2022)

In Robert Aickman’s novel Go Back at Once, the enigmatic and shadowy Virgilio Vittore personally annexes the Adriatic state of Trino and governs it ‘according to the laws of music’. Aickman sends his three female characters there from London, which proves to be an exciting, anarchic and surreal experience. Arguably, this is the best part of the book, where the author is able to explore a fantasy that was close to his own heart: the establishment of a society with the Arts at its centre. It is run by an ‘enlightened’ individual, rather than a bothersome democracy.

Gabriele D’Annunzio, Comandante of the Carnaro

Vittore was based on the Italian poet and author Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938), regarded in his home country as a war-hero, and who, in 1919-1920, as a part of the Italian nationalist reaction against the Paris Peace Conference, set up the short-lived Italian Regency of Carnaro in Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia). D’Annunzio entered the city with only a handful of soldiers and proclaimed himself Duce.

Fiume residents cheering D’Annunzio and his soldiers, September 1919

In Carnaro, D’Annunzio wrote the constitution, and Aickman quoted approvingly, ‘ “In the Regency of the Carnaro, music will be a religious and social institution”.’ D’Annunzio never called himself a fascist, but he is considered the forerunner of Italian fascism because his ideas and aesthetics were highly influential on Benito Mussolini. Aickman himself did not believe in democracy—he was an unashamed elitist, certain that some were born to rule over the majority. In Virgilio Vittore, Aickman offers us an example of how he believed an enlightened country could be run.

D’Annunzio would have felt vindicated when the independent Free State of Fiume was created by the Treaty of Rapallo on 12th November 1920, but he overplayed his hand. He ignored the Treaty and declared war on Italy itself. In retaliation, the Italian army attacked Fiume on 24th December, and the Royal Italian Navy commenced a bombardment. After five days of fighting, known as ‘Bloody Christmas’, the Fiuman legionnaires evacuated and on 29th December surrendered. The Free State of Fiume, however, lasted officially until 1924, when it was formally annexed to Italy under the terms of the Treaty of Rome.

Despite declaring war on his own country, D’Annunzio was able to retire to his home on Lake Garda where he spent his remaining years writing and campaigning. Although he influenced the ideology of Benito Mussolini, he was not directly involved in Italian fascist government politics. In 1922, he fell out of a window (it is not known if he was pushed), and was badly injured. He was ennobled by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1924 and given the hereditary title of Prince of Montenevoso. In 1937 he was made president of the Royal Academy of Italy, and when he died in 1938 (of a stroke) he was given a state funeral by Mussolini.

Despite declaring war on his own country, D’Annunzio was able to retire to his home on Lake Garda where he spent his remaining years writing and campaigning. Although he influenced the ideology of Benito Mussolini, he was not directly involved in Italian fascist government politics. In 1922, he fell out of a window (it is not known if he was pushed), and was badly injured. He was ennobled by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1924 and given the hereditary title of Prince of Montenevoso. In 1937 he was made president of the Royal Academy of Italy, and when he died in 1938 (of a stroke) he was given a state funeral by Mussolini.

Mausoleum of Gabriele D’Annunzio, at the Vittoriale degli italiani, in Gardone Riviera, on Lake Garda, Brescia, Italy. Photo by Daderot.

D’Annunzio’s remains were interred in a grand tomb constructed of white marble at Il Vittoriale degli Italiani (the shrine of victories of the Italians) at a hillside estate in the town of Gardone Riviera, overlooking Lake Garda. It is where he lived after his defenestration until his death. The estate includes his residence (the Prioria), an amphitheatre, D’Annunzio’s cruiser Puglia set into a hillside, a boathouse containing the torpedo-armed motorboat used by him in 1918 and a circular mausoleum. The Vittoriale is described variously as a ‘monumental citadel’ and a ‘fascist lunapark’.

Jutting out of the hilltop at at the Vittoriale degli italiani, the bow of the D’Annunzio’s cruiser Puglia. It points in the direction of the Adriatic, ‘ready to conquer the Dalmatian shores’. Photo: Federica Pinelli.

Robert Aickman travelled extensively in Europe after the Second World War, until his death in 1981. As he is known to have visited Mussolini’s tomb, it seems quite likely that he would also have visited Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Mausoleum.

The above is an expansion of material from Robert Aickman: An Attempted Biography by R.B. Russell.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Heather Smith, and Artellus, Ltd.

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are copyright Estate of Robert Aickman/British Library/R.B. Russell, and are not to be reproduced without permission and acknowledgement.

No comments:

Post a Comment