Philip Henry Gosse & Edmund Gosse (1857)

Edmund Gosse (1849-1928) was an accomplished and respected English poet, author and critic. Among many well-received books, he wrote a biography of his father, Philip Henry Gosse, and in 1907, aged fifty-eight, published a memoir of his youth, Father & Son, focussing on his relationship with his father. His family were very devout members of the Plymouth Brethren, and Philip Henry was a self-taught marine biologist. The primary interest in Father & Son is the relationship between the religious father (who cannot reconcile his fundamentalist faith with the new evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin), and the son who questions and rejects his father’s beliefs. His father is a looming presence over Gosse’s childhood and could even be considered something of a tyrant, but the relationship is not without a measure of love.

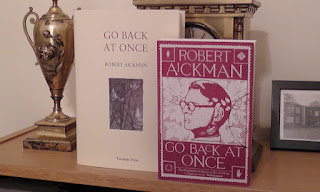

In August 1971 The Folio Society asked Robert Aickman to write an introduction to their reissue of Father & Son. Aickman noted that this request was, no doubt, prompted by his own autobiography, The Attempted Rescue (1966), which had been compared favourably to Gosse’s classic memoir. Despite a tight deadline, Aickman submitted eight typed sheets, for publication in 1972.

Father & Son by Edmund Gosse, Folio Society, 1972

I do not know why The Folio Society did not use Aickman’s introduction, which is interesting and entertaining. However, it is somewhat rambling, and in many respects says more about the introducer than the author. Aickman, for example, states that the central theme of the book is ‘the right to be an individual’, which, it can be argued, is only a part of what Father & Son has to offer the reader. Aickman also uses the introduction to complain about his usual bug-bears (‘the great modern trinity, technocracy-overpopulation-egalitarianism’).

There are striking similarities between Father & Son and Aickman’s own The Attempted Rescue, but there are also important differences. Gosse’s father is a strong, charismatic personality and Gosse is obviously in awe of him. Aickman described Philip Henry Gosse as a 'unique and noble figure', and suggested that his own father was similar. But Father & Son is a coming-of-age book in which Edmund learns to reject everything that is most important to his father (a man who exemplified the contemporary dilemma of religious faith in a modern world). Aickman, however, seems to have lived a life in thrall to his father until 1941, when Robert was twenty-seven, and his father died. William Arthur Aickman appears to have been a personality adrift in the world as he became more elderly.

Gosse wrote of his memoir, 'This is not an autobiography' and published the first edition anonymously. Aickman noted that Gosse left him with the ‘impression that every single word had been fought for to express the exact truth as the author felt it’. (My italics.) This acknowledges that Father & Son might not have been precisely factual (and did not need to be). It is interesting that Ann Thwaite’s 2002 biography of Philip Henry Gosse suggests that Edmund’s father was a far more gentle, loving and thoughtful man than the one portrayed by his son. Far from being sequestered and melancholic, Edmund’s childhood appears to have been full of affection and warmth, and he was surrounded by many friends.

Robert Aickman with his mother and father, 1920s

There is a fascinating similarity between Edmund Gosse and Robert Aickman, for Aickman attempted to persuade readers that his own childhood was lonely, with his mother sick and his father domineering and eccentric. However, Aickman himself admits in The Attempted Rescue that he had friends throughout his early years, attended parties, was popular at school, and saw a great deal of his wider family. Some members of his family thought his descriptions of them highly inaccurate, and it is quite probable that Aickman would have excused any exaggerations and embellishments as the truth ‘as the author felt it’. Such judicial management of information would, of course, only serve to cement Aickman’s similarities to Gosse, whom Aickman described as a Grand Old Man in the field of letters—a description that Aickman would have been delighted to receive himself.

A melodramatic Four Square paperback edition from 1959

Robert Aickman: An Attempted Biography by R.B. Russell is available now.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Heather

Smith, and Artellus, Ltd.

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are

copyright Estate of Robert Aickman/British Library/R.B. Russell, and are not to

be reproduced without permission and acknowledgement.