Tartarus Press have just announced new editions of The Sound of His Horn and Other Stories (first published 1952) and The Doll-Maker and Other Tales of the Uncanny (1953) by ‘Sarban’, joining a third title, Ringstones and Other Curious Tales (1951) already available. These three highly original volumes of supernatural fiction are notable for several reasons.

Written in the 1940s and 1950s, the stories have all the qualities of the earlier, classic age of the uncanny in literature. Sarban specifically acknowledged the influence of H.G. Wells and Walter de la Mare, and we know he also read John Buchan, Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany, among others.

The attention to atmosphere and to a distinguished style that he must have learnt from these past masters is everywhere evident in his work. There is, for its time, a slightly old-fashioned feel to his prose, but this means it will appeal greatly to admirers of the late nineteenth century and Edwardian classics. The title story of ‘Ringstones’, for example, invoking elemental creatures among Roman and prehistoric remains on a Northern English moor, would not be out of place as part of the Machen canon. The travellers’ tales of great beasts and implacable gods in the same volume could be from a Dunsany collection.

But he is far from simply an imitator. Sarban also had a strong sense of more modern concerns. In The Sound of His Horn, a timeslip fantasy into a world where the Nazis have won, he shows a sound insight into the Völkisch mentality underpinning the movement and where this might well have led: to the hunting of human prey in special forest reserves.

There are simply not many working-class writers in the field of classic fantasy and supernatural fiction. Almost all come from gentry, clergy or the professions. It is true that, nevertheless, in some cases their families had fallen on hard times and they experienced real hardship: Arthur Machen, the son and grandson of priests, lived for a while in penury in a London garret on dry bread, green tea and tobacco.

But of the other leading figures, we might think only of Walter de la Mare, who worked at dreary tasks as a statistical clerk in an oil company before a Civil List pension for his poetry set him free: and Charles Williams, the son of a London clerk, who made his way in publishing as well as prolific writing (prolific, partly because he needed the money): people still commented on his lower-middle-class accent.

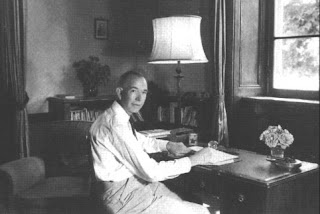

Sarban was John William Wall, and although there were some family origins in farming in Lincolnshire, Sarban’s father was a railwayman, and the young Wall grew up in what he described as the ‘meanly dingy’ town of Mexborough, South Yorkshire. He won admission to the local grammar school, where ambitious and forward-looking teachers recognised his potential and coaxed him on to university, aided by a scholarship and local authority support.

No comments:

Post a Comment